After learning about the Hohokam near the airport and the considerable history and talents on display at the Heard Museum in Downtown Phoenix, I decided that this year we would spend some time exploring Scottsdale. We're not the type to buy things in boutiques or art galleries, but we enjoyed walking around the Old Town and looking at the shops and the art. There were the requisite statues and paintings of bucking broncos, but our favorite was probably "One-Eyed Jack." He's a "wild" jackrabbit and a lucky symbol of rebirth.

After a nice lunch dining alfresco, Dear Husband and I walked down to

Western Spirit: Scottsdale's Museum of the West. Here is the museum entrance and a shot from its central sculpture garden. It contains a variety of exhibits, such as a portion of a Pittsburgh man's collection of Western memorabilia. The docent who gave our tour tried to make a joke about the man having "a serious disease"--which turned out to be "the collector's bug." It was a "Please laugh" moment.

Anyway, he told us a lot of stories about Annie Oakley, (1860-1926) who would shoot glass pigeons like these, blown by Tiffany's and stuffed with feathers. She was born and died in Ohio, although she and her husband built a house in Cambridge, MD, on the Eastern Shore late in life. I didn't know that she had been in a railway accident in 1901 (it made me think of Frido Kahlo, although her bus accident was in 1925).

The docent was also big fan of John Coleman's (1949- ) art, especially his bronze statues. This one, called "Gall, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, 1876" for the year of Custard's Last Stand, depicts the warriors as accurately rendered as he could from photographs and descendants. The docent described each man as using what he had acquired from white men to defeat them: a bleeding heart hatchet, the desperation of having lost their families, repeating-action rifles, and in the case of Sitting Bull, using the French he learned at an Indian School to read about Napoleon's strategies of war.

Downstairs was also a large exhibit on a white man's photographs of southwestern Native Americans and their cultural products, as hew as sure that "they were a vanishing race." "Light and Legacy: The Art and Techniques of Edward S. Curtis" showcases some of the more than 40,000 images Curtis (1868-1952) made west of the Mississippi and along the Pacific Coast in the process of creating 20 volumes and 20 portfolios on The North American Indian (1907-1930).

The section "Turning Copper in Paper" talked about the various kinds of image techniques he used: photogravures, glass and copperplates, goldtones (actually made with copper), platinum prints, silver bromide and gelatins, and cyanotypes.

Upstairs were a number of sections on historical artefacts (Buffalo Bill commissioned the painting on the right). Below are Navajo "chief blankets," a craft they originally learned from the Pueblo Indians, that demonstrate the evolution of Native design.

There were a number of representative paintings from the Taos School, founded by two Europeans, one of whom summered in Arizona and wintered in Europe (yes, you read that right).

After so many images made by other people, I decided to focus on Native American self-portraits. This is a Crow blanket from pre-1850 on which the artist has depicted himself as a blue warrior defeating a variety of enemies over the years.

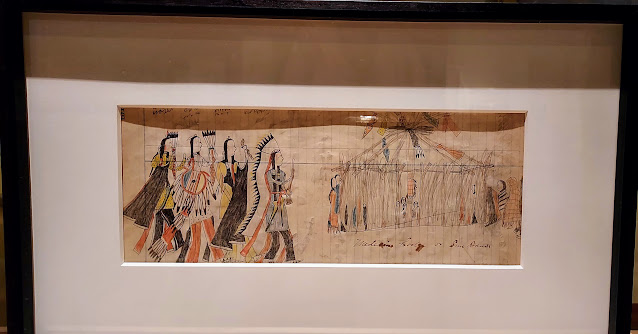

Here are some examples of what is called "Plains Indian Ledger Art," drawn on the pages of ledgers from the 1860s-1880s.

Finally, there was a retrospective of photographic portraits of ranchers and their families.

I chose to do the matte side of the succulent puzzle, figuring it would be easier to solve with four discrete sections, but after sorting the pieces, it turned out that the tiny repeating details of the petals may have made this the harder of the two options. Ah well. "Next time" I can do the other side.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your comments let me know that I am not just releasing these thoughts into the Ether...