Editor's note: My residency program decided to do the American Bar Association's 21-day Racial Equity Habit-Building Challenge. We've split up the days to read, listen, and write a reflection to share. This is the first of my two contributions; here is the second.

|

Cheryl I. Harris is the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation Chair

in Civil Rights and Civil Liberties at UCLA School of Law |

The reason I am a historian of the body is because in college I was assigned to read

Barbara Duden’s book, The Woman Beneath the Skin. It is an English translation of her exhaustive study of the case records of one early modern German doctor. After sifting through hundreds of patient encounters, Duden realized that these women had a completely different relationship with their bodies than she did with hers. Namely, they saw themselves as deeply embodied, as one with their mortal flesh. It was porous flesh, to be sure, subject to humidity, wind, fright, and the astrological signs. Pre-modern individuals

were their bodies. By contrast, Duden described herself as having a modern conception of her body as separate from herself: I exist in my body, but I am not my body (to paraphrase). It was a revelation to her, and to me.

This brings up all sorts of questions about the relationship between an individual patient and her illness. Is cancer “self”? Is depression or anorexia nervosa some true expression of a hidden ego (or, better, id)? Or is it a separate entity that represents a common foe for patient, family, and physician? What about conditions that fall under the broad rubric of “disabilities”? Under the medical model of disability, “a handicapped person” was common parlance. But with the rise of person-first language, we started to say “a person with a disability,” because they were themselves first. A disability was just one of many traits they possessed—or, alternatively—disability was created when society around them did not accommodate their differences (wheelchair users aren’t “disabled” if the built environment is accessible to them, for instance). More recently, some individuals have returned to using phrases such as “an Autistic person,” because their Autism is intrinsic to their sense of self.

What about race? What about whiteness? Am I a woman who is white? A white woman? A wyt woman? Is my whiteness just one of many traits or a core, inextricable part of my identity? Cheryl I. Harris’s landmark 1993 essay in the

Harvard Law Review, “

Whiteness as Property,” demonstrates how white Americans have constructed whiteness as a collection of entitlements enshrined into law that they inherit with their light skin and from which they profit. She draws examples from the dispossession of Native Americans and the enslavement of Blacks; interprets numerous legal decisions from the standpoint of whiteness as a property conferring status and material privileges; and concludes by arguing that well-done affirmative action as part of a plan for (re)distributive justice could redress some of generations of inequality engendered by legalized white supremacy. Although lengthy (80 pages), the essay and its voluminous footnotes are eminently quotable. Truly a tour-de-force, I will summarize.

Let me begin by recognizing the fact that I currently occupy land that should belong to

the Haudenosaunee or Longhouse Confederacy. You see, a crucial early step in the development of whiteness as property was the argument that only white people could own property. European settlers who wanted Native lands reasoned that although Native Americans were already living on the land, because they held it in common rather than individually, they actually held nothing at all. This argument against the commons originated in 13th-century England, when a few wealthy people started fencing off land for their private use. Enclosure gained steam in the 17th century, when small, scattered tracts were consolidated and divided by hedgerows for greater efficiency. While landowners were thus able to produce more than they needed and sell it for profit, the landless had less, and less fertile, ground to till or to graze. They either scraped by as subsistence farmers or joined the exodus to growing cities as labor for capital to exploit in burgeoning factories. There they owned their wages but not the excess value created by mixing their labor with the employer’s resources. By both common law and book law, could Native Americans “own” land if it wasn’t fenced in? Even if a tribe could hold a deed, could it transfer ownership to individual settlers, or only to whichever government offered to make (and break) treaties with them? And so white people spun the tale of “virgin” land in the New World just waiting for Europeans to possess it “the right way.”

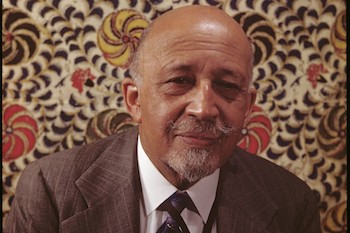

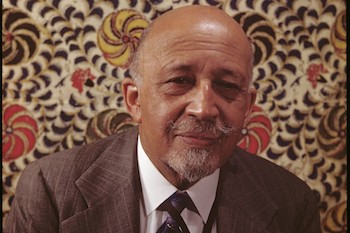

Possession might be 9/10 of the law, but 1 drop of black blood was sufficient to disqualify a person from having personal liberty. This theory is called “hypodescent.” Reason might suggest that majority rules, whether in a democracy or in an individual’s ancestry, but because it was beneficial to white people to pretend that their blood was “pure,” they stood mathematics on its head and decreed that any non-white heritage was sufficient to disbar someone from membership in the white “race.” Similarly, although European societies typically followed patrilineal inheritance, because it was more economical for white slave holders to rape and impregnate female slaves than to purchase black people on the market, they decreed the matrilineal transference of enslavement. Blackness become the marker of the most extreme form of otherness, the potential to be held in bondage. As capitalism and the oppression of the free poor grew over the course of the 19th century, white laborers were able to draw what W.E.B. Du Bois called a “public and psychological wage”: “the wages of whiteness” were the assurance that there would always be someone who was worse off than they were:

aka “at least I’m not black.” This divide-and-conquer strategy has hamstrung the labor movement ever since.

|

| William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868-1963) |

Slavery is in our past, but as William Faulkner famously wrote, “the past is not dead. It not even past.” Harris continues by dissecting two well-known Supreme Court cases that hinged on race. In

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), shoemaker Homer Plessy argued that he should be allowed to ride in the white train car, because he passed as white. Making him ride in the “colored” train car because of his 1/8 black ancestry prohibited him from earning all the (im)material benefits of being assumed to be white in Louisiana, such as the ability to earn a decent living in a “white” job. One of Plessy’s attorneys described whiteness as “the most valuable sort of property, being the master-key that unlocks the golden door of opportunity” (as qted on 1748). The Court disagreed, arguing that if Plessy were white, he could be compensated for the temporary slight to his reputation with a fine from the rail company, and if he were not white, then he was not legally entitled to any of the benefits of whiteness, either riding in train cars or being compensated for slights to his reputation. This ruling allowed individual states to legislate their own racial definitions and upheld discriminatory laws that permitted “separate but equal.”

In

Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court finally admitted that “[s]eparate … [is] inherently unequal” BUT allowed states to enact material changes “with all deliberate speed.” You can guess how quickly they moved: like a herd of land tortoises. Unfortunately,

Brown was one of those instances when people could argue “there is no more racism,” as if the mere fact of declaring that children should attend integrated schools were sufficient to override generations of lower-quality education, redlining, discriminatory hiring practices, the wholesale destruction of established black neighborhoods (::cough::

Pittsburgh's Hill District), school funding based on property taxes, and—of course—the ensuing white flight out of urban areas funded by federal dollars for highways, federal loans for (white) homeowners, federal subsidies of steel for those ridiculous Cadillacs, etc.

Harris argues that affirmative action policies are a way to break down white expectations that the status quo and all their privileges continue to be protected. Where white support of affirmative action goes awry is when “innocent whites” complain that they should not suffer individually for the sins of their fathers, even though they continue to enjoy the spoils. They seem to be saying, better that black people continue to suffer in a “post-racial” society than that a specific white person loses something. Consider

University of California v. Bakke (1978): white applicant Alan Bakke felt that he had a right to attend University of California, Davis School of Medicine, but rather than challenge the 5 seats reserved as favors for well-connected applicants, he went after the 16 seats reserved for students from disadvantaged or minority backgrounds. He won. If we focus on what a few “innocent whites” lose instead of what affirmed black applicants gain, then not only do we miss the opportunity to right past wrongs, but we are centering whiteness. Again.

Thus, Harris defines whiteness as the ability to use trickery and force to own land, people, and the fruits thereof. It was ability to write these inequities into law. It was the privilege to sit on the juries that enforced those laws. And “whiteness became the quintessential property for personhood” (1730). It became the one trait that entitled a person to be their own individual; to possess self-determination, the land of Native Americans, the bodies of Black Americans, and the profits of workers; to appropriate the cultures of others as sports mascots and as Halloween costumes; and the right to bear arms, peaceably assemble, drive, walk, and breathe without molestation from the police. Whiteness is the colorblindness to assume that because I have not enslaved a black person, I am not racist. It is the smug assumption that if Blacks and Whites are not equal it is not my fault, and that I do not and should not have to give anything up to rectify ongoing disparities.

Whiteness is something that I have, whether I want it or not. Unlike my modern sense of self, it is an inalienable part of me, an immutable property. I did not choose to be born into this body, and I do not have to do anything to accrue the benefits of my skin tone. However, I can and must choose to amplify the voices of people of color rather than talking over them; minimize my presence if it will maximize their authority; and take only what I need and redistribute the rest, whether that is recognition, resources, or (meta)physical space. Cheryl I. Harris did us a great service by laying bare the ways in which the United States was built on legalized theft and oppression based on something as ultimately inconsequential as the melanin content of one’s skin. Although Lady Justice claims not to see color, she has never been blind.